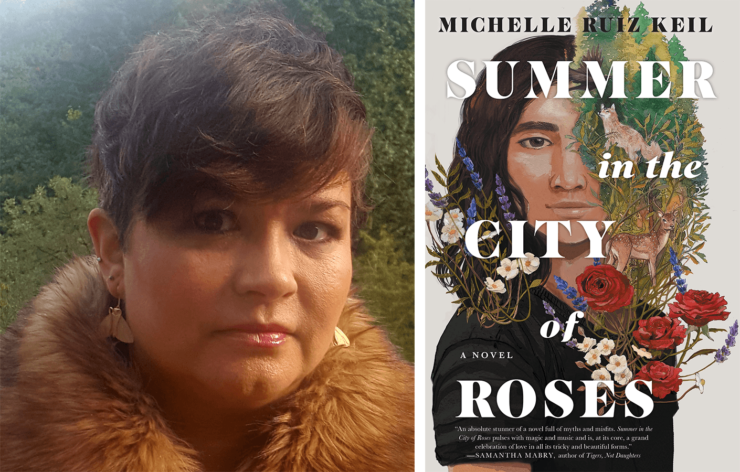

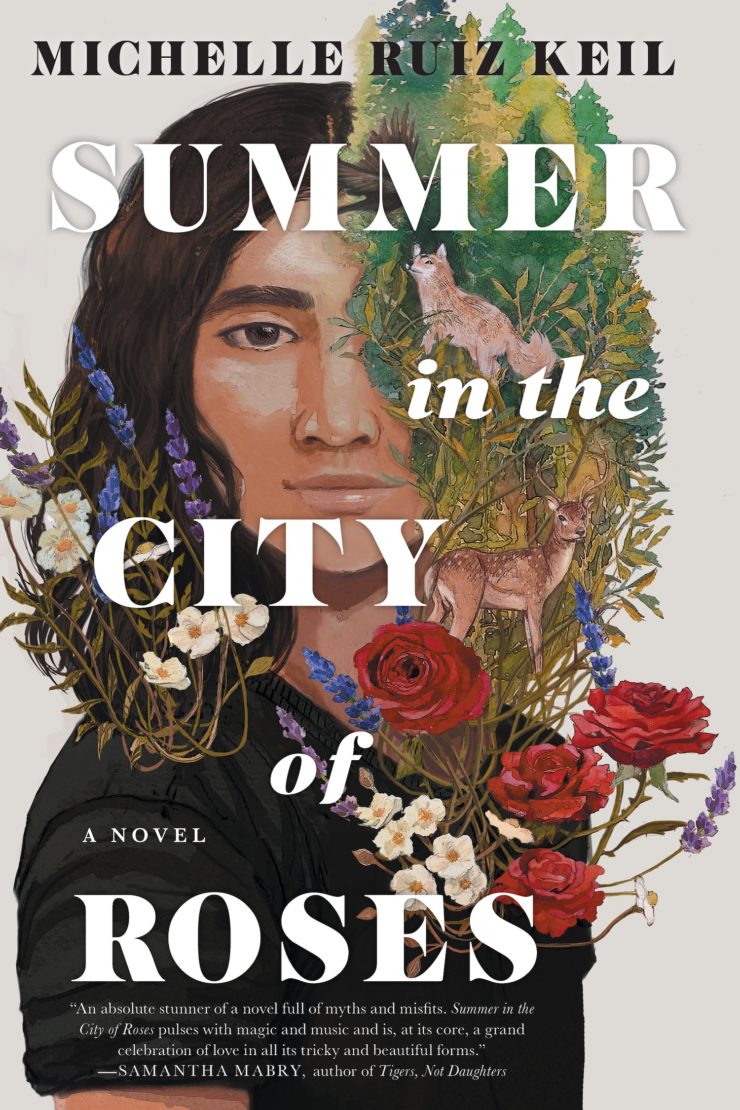

We’re thrilled to share the cover and preview an excerpt from Summer in the City of Roses, a new novel from Michelle Ruiz Keil—publishing July 6th with Soho Teen.

Inspired by the Greek myth of Iphigenia and the Grimm fairy tale “Brother and Sister,” the novel follows two siblings torn apart and struggling to find each other in early ’90s Portland.

All her life, seventeen-year-old Iph has protected her sensitive younger brother, Orr. But this summer, with their mother gone at an artist residency, their father decides it’s time for fifteen-year-old Orr to toughen up at a wilderness boot camp. When he brings Iph to a work gala in downtown Portland and breaks the news, Orr has already been sent away. Furious at his betrayal, Iph storms off and gets lost in the maze of Old Town. Enter George, a queer Robin Hood who swoops in on a bicycle, bow and arrow at the ready, offering Iph a place to hide out while she figures out how to track down Orr.

Orr, in the meantime, has escaped the camp and fallen in with The Furies, an all-girl punk band, and moves into the coat closet of their ramshackle pink house. In their first summer apart, Iph and Orr must learn to navigate their respective new spaces of music, romance, and sex work activism—and find each other to try to stop a transformation that could fracture their family forever.

Told through a lens of magical realism and steeped in myth, Summer in the City of Roses is a dazzling tale about the pain and beauty of growing up.

Buy the Book

Summer in the City of Roses

Michelle Ruiz Keil is a Latinx writer and tarot card reader with an affinity for the enchanted. Her critically acclaimed debut novel, All of Us With Wings, was called “a transcendent journey” by The New York Times. She is a 2020 Literary Lions honoree and the recipient of a 2020 Hedgebrook residency. A San Francisco Bay Area native, Michelle has lived in Portland, Oregon, for many years. She curates the fairytale reading series All Kinds of Fur and lives with her family in a cottage where the forest meets the city.

1

The First Acquaintance With A Part

It’s the middle of summer, but of course there’s rain. Clouds race past, covering and uncovering the moon. Iph’s high heels squish with water, insult to the blistered injuries that are her feet. Her mother’s cashmere sweater, already two sizes too small, is now a second skin. She stops at a wide, busy street that might be familiar if she’d remembered her glasses. But those, along with her purse, are far away, sitting innocent and hopeful on the white tablecloth in the hotel banquet room.

A guy across the street beams a glance her way and walks backward a few steps so he can keep on looking. She concedes a point to Dad. Earlier tonight, when she swanned into the living room in her white movie-star dress, he nodded approval at the first impression—glamorous but appropriate—followed by a jaw-drop of horror when his eyes reached her chest. Iph turned without a word and got the sweater out of her mother’s closet—oversized and beachy on gamine Mom, not-quite-button-uppable on Iph. Although Mom has trained Dad against the sexism of policing his daughter’s clothes, Dad insists on a basic truth: Men are malákes. Disgusting. A wolf whistle follows her around the corner, bringing the point home.

Iph turns away from the busy street—Burnside, she thinks, squinting at the blurry sign—and walks back the way she came. A car drives by a little too slow. More men, more eyes. This never happens in Forest Lake. She isn’t scared… but maybe she should be? “The trick to bad neighborhoods,” Dad once told her, “is to act like you belong.” She was twelve or thirteen then, brought along to pick up a load of salvaged building materials from a part of the city people called Felony Flats. Staring out the rain-spattered window of his truck at the small houses with their peeling front porches and dandelion gardens, Iph wondered what exactly made a neighborhood bad.

An older woman wearing a blanket instead of a raincoat shuffles past on the other side of the street. A car whizzes by, blasting the Beatles. “Yellow Submarine” to go with the weather—a childhood road-trip favorite. Iph would give anything to be in that silver Volvo now, sharing a pillow with Orr in the back.

She stops. She can’t think about her brother. Can’t stand here crying in the rain with no coat.

She takes a deep breath and starts walking again. Each step cuts like her gold heels are the cursed shoes of a punished girl in a fairy tale. She passes an alley. The same creepy car that slowed down before is turning in. A group of kids, some who look younger than her, are leaning against the wall, smoking. Iph hurries by. The scent of wet asphalt and urine wafts toward her on the wind. Iph wills her nose to stop working. So yeah, this neighborhood is probably what her father would call bad. She should go back and face him. Find some way to make him change his mind. But there’s no making Dad do anything, not when he thinks he’s right.

It’s humiliating how useless she is out in the real world. Like a jewelry-box ballerina waiting to be sprung, she’s dreamed her life away in her pink suburban bedroom, sleeping as much as possible, rewatching her favorite movies, and rereading her favorite books. She always thought she’d be one of those kids who got their driver’s license the day of their sixteenth birthday so she could drive into Portland whenever she wanted. Like Mom, she loved the city. But sixteen came and went without even a learner’s permit.

Once, years ago, Iph heard Mom talking on the phone to her best friend. “If I’d have known how white it was in Oregon,” she said, “I would’ve made Theo transfer to NYU and raised the kids in Brooklyn.”

City-girl Mom made the best of it. Portland was still mostly white, but more liberal and diverse than Forest Lake. She’d taken Iph and Orr into Portland weekly since they were little—for Orr’s cello lessons and Iph’s theater camps, trips to museums and plays and record stores and summertime Shakespeare in the Park. Most often, they go to Powell’s, the enormous bookstore downtown that covers an entire city block. The streets around Iph look a little like those.

But really, all the streets in downtown Portland look like this—art deco apartment buildings crowded next to the sooty turn-of-the-century low-rises Dad calls brickies; parking lots next to Gothic churches; nondescript midcentury offices and newish high-rises, shiny with rain-washed glass. In Portland—or everywhere, really—Iph has been content to let Mom do the driving, the thinking, the deciding. They all have. And now, after two weeks without her, their family is broken, and Iph can’t imagine a fix.

She stops at an intersection and squints at the sign. The streetlight is out, so it’s only a blur. Something hot is oozing from her heel. Her fingertips come back bloody. Blood has always made Iph feel faint. Sometimes, she actually does faint. She looks for somewhere to wipe her hand.

On the corner is a box with the free weekly paper. She rips the cover page in half and does her best with the blood. Doesn’t see a trash can and settles for folding the sullied paper and sending it down the storm drain—a lesser form of littering, she hopes. She breathes through the pain in her feet. She needs a break. A plan. She leans against the nearest wall. The stucco snags Mom’s sweater. What a waste. And for nothing. The whole outfit, the whole evening, was a con.

Iph cringes at her three-hours-ago self, proudly walking into that hotel on Dad’s arm. When the band began “Fly Me to the Moon,” he even asked her to dance. They waltzed easily, him singing the words so only she could hear them. When she was little, they’d bonded over Ol’ Blue Eyes, which is what Dad calls Frank Sinatra. He twirled her and dropped her into a dip, a routine from their father-daughter dance in middle school. His co-workers smiled, and Iph remembered what it was like when she and Dad were close.

“Sweetie,” he said as the song ended, “I need to talk to you about something.”

***

2

Sensing The Hunter’s Footstep

Orr sees stars. Thinks about the phrase, He saw stars. Words for a cartoon head injury, a cast-iron pan to the head. He gags—a sudden rancidness. The scent of an unwashed pan. The way the kitchen smells when Dad’s away and Mom leaves the dishes in the sink all week. But this isn’t kitchen grease. Or a dream. It’s the smell of the men pulling him from his bed.

A sack covers his head. His arms ache where hands grip him, lift him. The upstairs hall tilts by in the shadow world outside the thin black fabric. Orr remembers to scream. He flails, knocking into a chair, the countertop. He reaches out to the bumpy plaster wall of the entryway and claws at the worn spot next to the phone, but the men yank him away.

The alarm beeps its familiar goodbye as the front door slams shut. Orr quiets. Listens. The night is cool and smells like rain. He is strapped into a vehicle. Like Agent Scully on The X-Files, he is being abducted.

His sockless feet are clammy in his shoes, tied too tight by his kidnappers. His breathing is shallow. A meltdown builds. He reaches inside for the ghost in him, the thing Mom calls tu alma—his soul—but the ghost is gone, hiding or fled.

With his index finger he traces the map line of the West Coast on his leg, from British Columbia to Baja California. Questions form: Where am I? Where are they taking me? And why?

He breathes a little deeper. Wiggles his toes, tells them it’s okay. Waits for the world to settle.

He is in a large car, possibly a van. The cracked vinyl seat is a fanged menace under the worn flannel of his too-short pajama pants. Summer rain hisses under the tires. The radio switches on, a sports station blaring. Orr reaches for music—his battered Klengel, Volume 1 with its old-world yellow cover and pages of punishing drills he’s grown to love. He recalls every detail of the slick round stickers his teacher placed on the fingerboard when he was a beginner. He remembers the deep cramping of new muscle in his wrist and hand. His right elbow crooks around an invisible bow. His legs shape the cello’s curves until he can almost feel its purr.

The radio drones on and on. Baseball. Orr knows more than he cares to about the game. For Dad’s sake, he’s tried to love it. The announcer’s voice is deep and comforting. The rhythm of thwack, cheer, talk surprisingly helps Orr think. Details coalesce. The silent house, the men. The way he never heard them enter. The alarm’s familiar sequence of beeps, because… because…

They knew the code.

They knew.

Orr narrows his eyes in the solitude of the hood. Fucking Dad. That’s what Iph would say. This whole ordeal is because of Dad and that awful brochure.

The van stops. Orr is unsure how much time has passed.

“Okay, kid,” a voice says, and the sack is pulled from Orr’s head.

The waxing moon is bright as a bare light bulb in the star-exploded sky. Crickets chirp. Frogs harmonize in the deep forest hush. The gravel parking lot is a stark landing pad in a tree-circled compound. Orr nods. This has been a long time coming.

Finally, here he is: a prisoner at the Fascist Reeducation Facility for Inadequate Specimens, also known as the Meadowbrook Rehabilitation Center for Boys.

Boot camp.

He’s heard of it, of course. A place for kids who do drugs or kids who got into fights—kids with something they need to change. What is Orr supposed to change? He doesn’t get into fights. Has no interest in drugs. He’s quiet, but silence is part of him, heads to the tails of his music.

The driver closes the van. Another man guides Orr toward a building that looks like some sort of lodge. A third walks ahead. This one is taller than the others, with a back like a bull’s. One second, Orr is fine. Then he’s not. He sees now that his calm in the van was only his mind’s clever ruse to protect himself and fool the men. Sound boils in the tar pit of his stomach, but Orr won’t let it out. It’s an experiment, an untested suggestion from his therapist: Contain the meltdown without dissociating. Talk to it. Make it your friend.

The lodge looms closer. The mountain silently watches. Orr morphs the meltdown into a tactical step. Sound transmutes to animal knowing. He feigns a slip, a twisted ankle. The man releases his arm and bends down.

After that, Orr doesn’t think. He just runs.

Excerpted from Summer in the City of Roses, copyright 2021 by Michelle Ruiz Keil